Muso Gonnosuke Jinja & Kamado Jinja at the foot of Mount Homan, near Dazaifu, Kyushu Japan

From Wikipedia: History of Shinto Muso Ryu [10]

Shinto Muso-Ryu ( 神道夢想流 )[1] is a traditional (ko-ryu) school of the Japanese martial art of jojutsu, the art of handling the Japanese short staff (jo / tsue). The art was created with the purpose of defeating a swordsman in combat using the jo, with an emphasis on proper distance, timing and concentration. Additionally, a variety of other weapons are also taught within the overall curriculum.

The art was founded by the samurai Muso Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi (夢想 權之助 勝吉, fl, c.1605, dates of birth and death unknown) in the early Edo period (1603–1868) and, according to legend,[1][2] first put to use in a duel with Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵, 1584–1645).

The original art created by Muso Gonnosuke has evolved and been added upon ever since its inception and up to modern times. Mainly as a private/secret martial art practiced by the military police of the Kuroda han in Fukuoka.

Today the rich curriculum of Shinto Muso Ryu includes approximately 64 sword/Jo kata. As well as almost 80 related weapons kata. All of these are divided into specific sets/groups designed to highlight specific lessons and guide a student towards a comprehensive understanding of this weapons system.

Shinto Muso Ryu Jo was successfully brought outside of its original domain in Fukuoka and outside Japan itself in the 19th and 20th century.

The spreading of Shinto Muso-ryu beyond Japan was largely the effort of Shimizu Takaji (1896–1978), considered the 25th [2] headmaster. With the assistance of his own students and the cooperation of the kendo[3] community, Shimizu spread Shinto Muso-ryu worldwide.

Muso Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi [10]

Musō Gonnosuke – Founder

Japan’s Warring States period (1467–1615), which had scarred Japan for almost 150 years, came to an end with the establishment of the authoritarian Tokugawa shogunate. This in turn ushered in an era of peace that would last for over 260 years, and ended with the overthrow of the shogunate in 1868.

The relatively peaceful Edo period took away the means of the samurai to fully develop and test their skills in actual battlefield combat. The role of the samurai would eventually change from being warriors, constantly fighting battles for their liege lord (daimyo), into the role of providing internal security with increasingly more bureaucratic duties.

Instead of fighting the frequent wars and battles of the old days, with the exception of the siege of Osaka in 1615 and the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637, many samurai resorted to duelling other samurai, with others going on the road as a wandering swordsman to test their skills against other swordsmen such as bandits and ronin. And still others would train in far away schools (ryu) to hone their skill.

One of the men who went on a warrior’s pilgrimage (musha shugyo) was Muso Gonnosuke, a samurai with considerable martial arts experience. It was said that during his musha shugyo he was never defeated until he met and challenged Musashi Miyamoto (more below).

Gonnosuke used his training in the arts of the sword (kenjutsu), glaive (naginatajutsu), spear (sojutsu), and staff (bojutsu), which he acquired from his studies in Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu[4] and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryu, to develop a new way of handling the jo in combat.[5]

Gonnosuke was said to have fully mastered the secret form called “The Sword of One Cut” (Ichi no Tachi), a form that was developed by the founder of the Kashima Shinto-ryu and later spread to other Kashima schools such as Kashima Jikishinkage-ryu and Kashima Shin-ryu.[1][6] His experiences, which would climax in his duels with the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, led him to create a set of techniques for the jo and establish a new school which he named Shinto Muso-ryu.[1][2]

The techniques were intended to be used against an opponent armed with either one or two swords. Among the advantages of the Jo is its superior length when matched against a sword. The extra length enables the wielder to keep the swordsman at a disadvantage and this is frequently applied in SMR.[1][2]

The legend states that Muso Gonnosuke fought two duels with Miyamoto Musashi and was defeated in the first, but victorious in the second, using his newly developed jojutsu techniques to either defeat Musashi or force the duel into a draw.

The first duel is described in the annals known as Niten Ki,[1] which is a list of anecdotes told about Musashi and compiled by Musashi’s followers after his death.[7] The Niten Ki describes the first duel to have taken place c.1610.

One of several legends states that after his defeat Gonnosuke withdrew to the Homan-zan mountain in the northern part of Kyushu, spent his days meditating and training, and underwent austere religious rituals.[7] There are several stories about how Gonnosuke received a vision of this new weapon, the Jo.

While resting near a fire in a certain temple, Gonnosuke heard a voice say “Be mindful of the strategy ‘the moon reflected in the water’ (suigetsu)”. In another, after one of his regular (exhausting) training sessions, he collapsed from fatigue and reputedly had a vision of a divine being in the form of a child, saying to Gonnosuke: “丸木を以って水月を知れ” – maruki o motte suigetsu o shire” – “Using a round stick, know the solar plexus”. [9]

He took it upon himself to create the jo deliberately longer, at 128 cm, than the average katana of the day (maximum length of swords were set by Tokugawa law – Buke Shohatto, at approximately 100 cm). Gonnosuke used that Jo length to his advantage in a fight. The tradition states that was his inspiration to develop his new techniques and to fight and defeat Musashi during their second encounter.[1][2] It should be noted that Gonnosuke spared Musashi’s life.

After the creation of his jo techniques and his establishment as a skilled jojutsu practitioner, he was invited by the Kuroda clan of northern Kyushu (in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture) to teach his jojutsu to their warriors. Gonnosuke accepted the invitation and settled there.[1]

Fukuoka Castle [11]

Fukuoka Castle [13]

Fukuoka Castle & Haruyoshi Gate/area . Click for larger image. [13]

The Secret Art of the Kuroda Clan (1614 – 1871)

After Gonnosuke’s death, his jojutsu would become a closely guarded secret (oteme-waza) of the Kuroda clan, and forbidden to be taught anywhere but within its domain and only to specially selected people within the warrior-class.[1] This was not an unusual practice in the Edo period.

The main students of Gonnosuke’s art were the men charged with policing the Kuroda clan’s domain (Kuroda-han). During this period other schools (ryu) were created and taught in the Kuroda-han, and in the various branches of the Shinto Muso-ryu system.[1]

During this period, two newly created schools which included the art of the police baton (jutte), and the art of restraining a man with rope (hojojutsu), were taught within the branches of the Shinto Muso-ryu as a complement to the arresting arts (tori-te).

After Gonnosukes death the art was mainly transmitted by the “Dangyo-shiyaku” (men’s arts instructor[1]), though not all branches of the Kuroda staff-traditions used the title of Dangyo-shiyaku.[1] The Dangyo-instructor position was, unlike the swordsmanship instructor (kagyo) a non-hereditary position[1] within the hierarchy of the Samurai.

The Dangyo-instructor in the Kuroda-domain was the charged with teaching the lower ranking warriors (ashigaru) in the arts of the staff (Jo), capturing/seizing/escaping (torite), gunnery (hojutsu) and rope (nawa)[1] among other martial arts. The position of Dangyo-instructor lasted until the abolishment of the Samurai and the feudal system in the 1860s-1870s.

Over time there would arise seven different lineages from the main Shinto Muso-ryu system.[1] These are collectively known as “The Staff of Kuroda” (Kuroda no jo). Of these seven branches of Gonnosuke’s jojutsu, only two would survive the ending of Japan’s feudal system in 1867 and the resulting socio-economic modernization, to be informally merged into a single line that is today the modern “Way of the Gods School of Muso” ( 神道夢想流 Shinto Muso-ryu ).[1]

The first split in the SMR occurred after the death of the fourth headmaster Higuchi Han’emon.[1] The split was the result of one of his licensed (menkyo kaiden) students, Harada Heizo Nobusada, breaking away to establish the “New Just School of Muso” (新とう夢想流 Shinto Muso-ryu) (later informally known as Kansai-ryu), while another licensed student of Higuchi Han’emon continued the original “True Path” line (later known as Moroki-ryu).[1]

For several years Gonnosukes art was passed on by these two lines. The “New Just” line continued until after the death of its headmaster Nagatomi Koshiro Hisatomo in 1772.[1]

Afterwards, the “New Just” line branched off into two separate traditions.[1] The primary reason for this branching, though indirectly, was the result of a restructuring of the living and training quarters of the warriors at the Chikuzen castle. The low-ranking foot soldiers (ashigaru) and the junior officers (kashi) were relocated to two separate areas of Fukuoka, partially due to the difference in the social status of the two groups.[1]

Each group would create new centers of training in their respective areas. This led to the establishment of two new branches from the “New Just”-line of jojutsu, each under their own respective head instructor.

These new lines were named Haruyoshi, led by Ono Kyusaku, and the other Jigyo, led by Komori Seibei, respectively. The two branches were named after the two respective areas of the castle (Maizuru Jo – 舞鶴城 – see map ) in which they trained.[1]

These new branches, Jigyo and Haruyoshi, were a reality by the early 19th century, but even though separate, all three lines appear to have been very similar in terms of techniques.[1] This was demonstrated when the Jigyo Branch was broken with the death of its head instructor Fujimoto Heikichi in 1815. Because of this, the Jigyo found itself without a fully licensed headmaster, [1] and without a successor from within its own organisation the line would have died out. However, Hatae Kyuhei, who held a full license in the Haruyoshi branch, would eventually revive the Jigyo branch and allow it to continue into the Meiji period (1868–1912).[1]

Meanwhile, the “True Path” had also fallen onto hard times as the tradition was broken with the death of Inoue Ryosuke in 1831. The similarities between the various “Staff of Kuroda”-traditions were again made clear when Hatae Kyuhei (who was an exponent of the Haruyoshi-branch and had also helped revive the Jigyo branch of the “New Just line”) revived the “True Path”. The “True Path” would, however, become extinct in the Bakumatsu era (1850–1867).[1] It was not until 1871 that the ban on teaching outside the Kuroda clan was lifted.

Shiraishi Hanjiro and the post-Kuroda period (1871- 1927)

With the abolishment of the shogunate in 1868 and easing of bureaucratic restrictions, Shinto Muso-ryu (and all the other martial arts of the land) was allowed to be taught outside the traditional family lands.

Despite this new-found freedom, however, it meant that the numerous economical benefits and patronage, which was a part of the traditional clan system, were abolished along with it. Because of this the numerous menkyo holders of SMR who had depended on the old system for financial support had no choice but to adapt themselves to this new Japan. Many of them left the traditional clan holdings, where their ancestors had lived for centuries, and made new lives and livelihoods for themselves.

The final abolishment of the warrior-caste and the feudal-system also led to a rapid modernization of Japan. During this era many of the old bushi (Samurai warriors of all ranks) had no choice but to abandon the old (and considered by most of the Japanese population of the time to be all but obsolete) martial arts altogether.

Throughout Japan most of the surviving traditions were kept alive, if only barely, by the former samurai and other enthusiastic individuals, the former which now had to find a new place (and a new source of income) in the new Japan, which frowned upon the old samurai way. Some of the old ryu, who were not as dependent on old samurai government sponsorship as others, fared better than others in the transition from samurai to the Western-style government.

During this transition period and beyond, various groups of former Kuroda bushi held sporadic meetings and training sessions in memory of the now bygone era. The old bushi present at these sessions included Uchida Ryogoro, Shiraishi Hanjiro and many of the former Dangyo (instructors) of the Kuroda clan.

Due to newfound cooperation between the surviving SMR-lineages there were several joint-licenses of the Haruyoshi and Jigyo-branches of SMR issued in the late 19th century. Shiraishi Hanjiro was one of those men who received a full Menkyo Kaiden license. By the end of the Meiji era, (1912), only Shiraishi was still active as a fully qualified exponent and dedicated teacher of the last two remaining Kuroda Jo lineages.[1]

Shiraishi Hanjiro was born in 1842 and was a lower class samurai. As a bushi, (collective name for all samurai warrior of all ranks), he learned jojutsu, kenjutsu and other warrior-arts as was expected of a samurai.[1]

After the fall of the samurai government, Shiraishi did his best to sustain the jojutsu tradition he had learned. He helped organise the post-samurai meetings and training-sessions of old Kuroda-warriors and would receive his full license in SMR-jojutsu during one of these sessions.[1] Shiraishi eventually opened up a dojo in Fukuoka City and taught the art there. Sometime in the late 19th century, Shiraishi started learning the art of Kusarigama (chain and sickle weapon) as taught by the Isshin-ryu tradition.[1] He would eventually receive a Menkyo Kaiden in this system and started teaching kusarigama-jutsu alongside jojutsu in his Fukuoka dojo.[1]

Shiraishi would award Menkyo Kaiden to several of his jojutsu students who carried on the tradition as a side-art (heiden bujutsu) to SMR-jojutsu.

Shiraishi’s dojo was located in then Hakata City. In 1876, Hakata City and nearby Fukuoka city was merged into a new city named Dai-Iti-Dai-ku (第一大区) and in 1878 further renamed as Fukuoka-ku (福岡区) by the Fukuoka Prefectural government.

Shiraishi would teach Shinto Muso-ryu there until his death in 1927.[1] Shiraishi’s senior, Uchida Ryogoro, decided to travel to Tokyo and teach and expand the art there while Shiraishi stayed in the designated Shinto Muso-ryu headquarters in Fukuoka.[1]

In the early 20th century Uchida Ryogoro arrived in Tokyo and set up shop, teaching Jojutsu to high-rankers in the Japanese society at the time. His students included Nakayama Hakudo (1873–1958),[1] founder of Muso Shinden-ryu, and Komita Takayoshi, founder of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (“Great Japan Budo Preservation Society”).[1]

It was during this time that Jigoro Kano was first invited to Fukuoka to observe SMR which would herald the cooperation between the two arts in Tokyo.[1] Uchida Ryogoro also taught at the Naval Officers Club and later at the Shiba Koen park. Ryogoro’s son, Uchida ryuhei, joined him in Tokyo and studied under his father there and was instrumental in developing his father’s TanJojutsu art into a working set of techniques.[1] Uchida Ryogoro died in 1921.

Uchidas efforts in Tokyo greatly assisted in establishing a connection with the various martial arts communities already based in Tokyo and would help pave the way to Shimizu Takaji’s own efforts at popularizing SMR and establishing a new SMR presence.

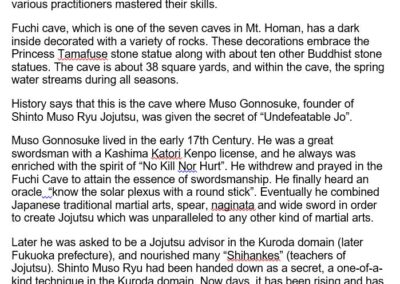

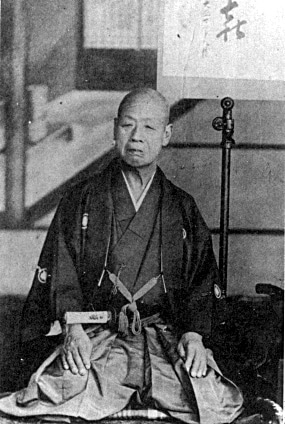

Shiraishi Hanjiro (1821-1927) [10]

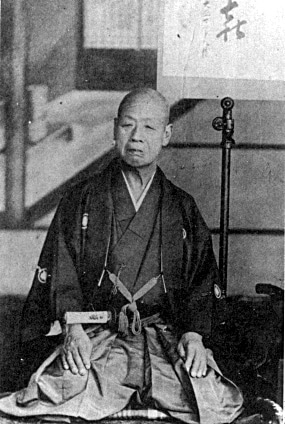

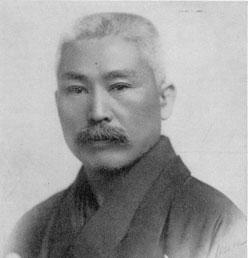

Uchida Ryohei, son of Uchida Ryogoro [12]

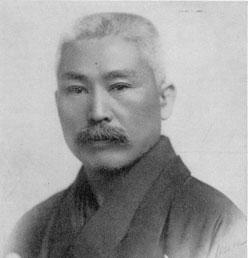

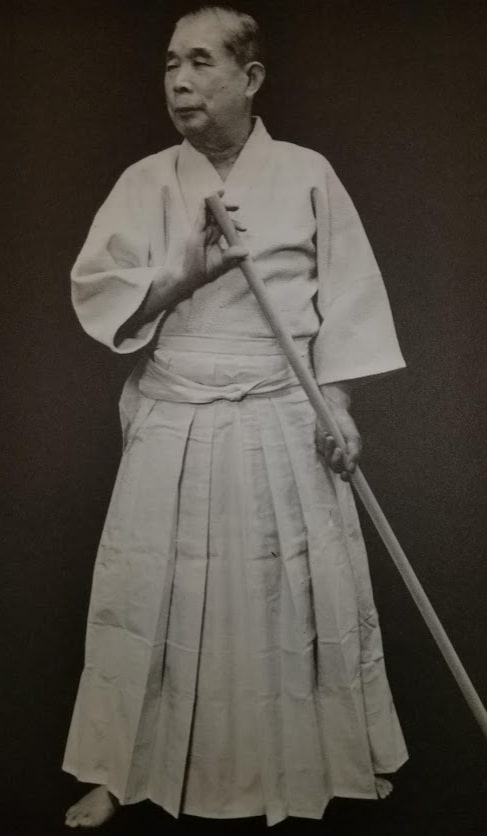

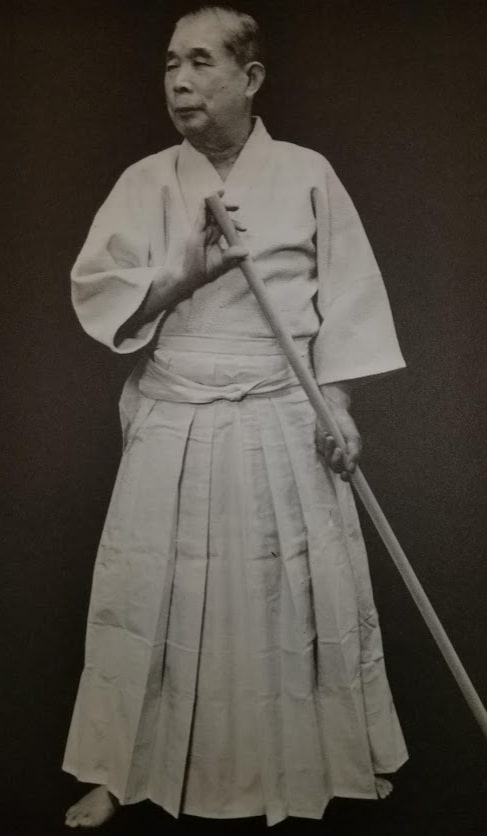

Shimizu Takaji (1898-1978) [16]

Police at Koban with Keisujo [14]

Shimizu Takaji era (1927-1978)

Shimizu Takaji was born in 1897 and came from humble origins, his family descending from a line of village headmen and minor officials.[1] In the aftermath of the abolishment of the samurai caste, Shimizu’s father would manage a small general store while Shimizu, after graduating from elementary school, took employment in a small factory at Hakata, where the Shiraishi Dojo operated.[1]

Shimizu started his training at the age of 17 (1914) under Shiraishi himself and quickly rose in the ranks, receiving the Mokuroku scroll in 1918 and the license of full transmission (Menkyo Kaiden) in 1920 at the age of 23.[1] Of the many students of Shiraishi there were three who became prominent in the aftermath of Shiraishi’s death. Shimizu Takaji (1898-1978), Takayama Kiroku (1893–1938) and Otofuji Ichizo (1899–1998).[1]

In the early 1920s Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, witnessed a demonstration of SMR and made an invitation to Shiraishi come to Tokyo and teach SMR there. Due to his advanced age Shiraishi declined to come in person and sent his student Shimizu Takaji instead.

Shimizu arrived in Tokyo in 1927. After a further demonstration of SMR-jo in front of the Tokyo Police Force technical commission, a decision was made to incorporate elements of SMR-jo for police-use.[1] The new system was named keijo-jutsu and intended for use with the special police unit Tokubetsu Keisatsutai.[1]

Shimizu started training the new unit in 1931. Now a permanent Tokyo-resident, Shimizu opened up his own dojo, the Mumon (No Gate) Dojo.

In 1929 Takayama Kiroku, with financial aid from the family of the late Shiraishi Hanjiro, opened a dojo in Fukuoka [1] and was named Shihan with Shimizu named fuku-shihan or “assistant master”. Shimizu by this time, however, was on his way to Tokyo in order to teach jodo. Takayama died in 1938 and Otofuji Ichizo took over as the new master of the dojo and of the Fukuoka-jo, a responsibility he held until his death in 1998.[1]

During the 1930s in Tokyo, Shimizu felt that the traditional way of teaching Jo was not suited for this new (and more numerous) generation of students. He realised that a better method of teaching Jo was required in order to properly teach ever increasing number of new students who had no previous experience of Martial Arts.

He took inspiration from Jigoro Kanos new Judo organisation and training-methods in order to, among other things, develop the twelve basic techniques kihon which would make SMR more appealing and approachable to the beginner-student.[1][2] These twelve basic techniques are still taught in most mainstream dojos today.

In 1940 Shimizu became the head of the Dai Nihon jodokai (Greater Japan jodo Association)[1] and he decided to rename the art from jojutsu to jodo in keeping with the trend of the time.

With the end of World War II in 1945, many martial arts were banned by the new government for fear that they might be used by ultra-nationalistic groups as a way to cause civil unrest.[2] The police-jo taught by Shimizu to the Tokyo Police force was one of the few exceptions and many other martial arts practitioners from before the war went to Shimizus dojo in Tokyo for training.[2] The police-jo were further developed in the 1960s when it was adapted for use in crowd-control with the Tokyo Riot police.

Shimizu, as had Shiraishi before him, has both been described as an SMR Headmaster due to their initiative and major contributions to SMR though neither Shiraishi or Shimizu received official appointment to such a position.[1] Shimizu would complete Shinto Muso-ryu’s transition from a localized bugei ryu to a national martial art and become the art’s greatest popularizer through his acceptance of foreign students and the establishment of jodo-organisations.[2]

Post-Shimizu Takaji era – 1978 to present

After the death of Shimizu Takaji in 1978, SMR in Tokyo was left without a clear leader or appointed successor. This led to a splintering of the SMR dojos in Japan, and eventually all over the world. With no single organisation or individual with complete authority over SMR as a whole, several of the various fully licensed (menkyo kaiden) SMR-practitioners established their own organisations both in the West and in Japan.

From the end of the Samurai reign in 1877 to the early 20th century, SMR was still largely confined, (though slowly spreading), to Fukuoka city on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu where the art first was created and thrived. The main proponent of SMR in Fukuoka during this time was Shiraishi Hanjiro, a former Kuroda-clan warrior (ashigaru), who had trained in and received a joint-license from the two largest surviving jo-branches of SMR.

Among Shiraishis top students were Shimizu Takaji, Otofuji Ichizô and Takayama Kiroku, Takayama being the senior. After receiving an invitation from the Tokyo martial arts scene to perform a demonstration of SMR, Shimizu and Takayama established a Tokyo SMR-group which held a close working relationship with martial arts supporters such as Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo.

Shiraishi died in 1927 and there now existed two main lines (or branches) of SMR. The oldest of the two was found in Fukuoka, now under the leadership of Otofuji with the one in Tokyo under Shimizu. Takayama, the senior of the three students of Shiraishi, died in the 1930s leaving Shimizu with a position of great influence in the SMR-scene as the senior-most student of Shiriashi, (Otofuji being his junior), that would last up to his death in 1978.

From these two lineages, the Fukuoka and the Tokyo, there stems today several SMR-based organizations all over the world. One of the largest is the All-Japan Jodo Federation (ZNJR), established in the 1960s as a branch of the All-Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR – Zen Nihon Kendo Renmei). The ZNJR was established to further promote Jo through the teaching of ZNKR Jodo, also called Seitei Jodo. Seitei Jodo remains the most widespread form of Jo in the world today.

Otofuji Ichizo (1899–1998) [16]

All Japan Kendo Federation – Seitei Jodo [15]

Muso Gonnosuke Jinja & Kamado Jinja at the foot of Mount Homan, near Dazaifu, Kyushu Japan

From Wikipedia: History of Shinto Muso Ryu [10]

Shinto Muso-Ryu ( 神道夢想流 )[1] is a traditional (ko-ryu) school of the Japanese martial art of jojutsu, the art of handling the Japanese short staff ( jo / tsue ).

The art was created with the purpose of defeating a swordsman in combat using the jo, with an emphasis on proper distance, timing and concentration. Additionally, a variety of other weapons are also taught within the overall curriculum.

The art was founded by the samurai Muso Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi (夢想 權之助 勝吉, fl, c.1605, dates of birth and death unknown) in the early Edo period (1603–1868) and, according to legend,[1][2] first put to use in a duel with Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵, 1584–1645).

The original art created by Muso Gonnosuke has evolved and been added upon ever since its inception and up to modern times. Mainly as a private/secret martial art practiced by the military police of the Kuroda han in Fukuoka.

Today the rich curriculum of Shinto Muso Ryu includes approximately 64 sword/Jo kata. As well as almost 80 related weapons kata. All of these are divided into specific sets/groups designed to highlight specific lessons and guide a student towards a comprehensive understanding of this weapons system.

The art was successfully brought outside of its original domain in Fukuoka and outside Japan itself in the 19th and 20th century.

The spreading of Shinto Muso-ryu beyond Japan was largely the effort of Shimizu Takaji (1896–1978), considered the 25th [2] headmaster. With the assistance of his own students and the cooperation of the kendo[3] community, Shimizu spread Shinto Muso-ryu worldwide.

Musō Gonnosuke – Founder

Japan’s Warring States period (1467–1615), which had scarred Japan for almost 150 years, came to an end with the establishment of the authoritarian Tokugawa shogunate. This in turn ushered in an era of peace that would last for over 260 years and ended with the overthrow of the shogunate in 1868.

The relatively peaceful Edo period took away the means of the samurai to fully develop and test their skills in actual battlefield combat. The role of the samurai would eventually change from being warriors, constantly fighting battles for their liege lord (daimyo), into the role of providing internal security with increasingly more bureaucratic duties.

Instead of fighting the frequent wars and battles of the old days, with the exception of the siege of Osaka in 1615 and the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637, many samurai resorted to duelling other samurai, with others going on the road as a wandering swordsman to test their skills against other swordsmen such as bandits and ronin. And still others would train in far away schools (ryu) to hone their skill.

One of the men who went on a warrior’s pilgrimage (musha shugyo) was Muso Gonnosuke, a samurai with considerable martial arts experience. It was said that during his musha shugyo he was never defeated until he met and challenged Musashi Miyamoto (more below).

Gonnosuke used his training in the arts of the sword (kenjutsu), glaive (naginatajutsu), spear (sojutsu), and staff (bojutsu), which he acquired from his studies in Tenshinsho-den Katori Shinto-ryu[4] and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryu, to develop a new way of handling the jo in combat.[5]

Gonnosuke was said to have fully mastered the secret form called The Sword of One Cut (Ichi no Tachi), a form that was developed by the founder of the Kashima Shinto-ryu and later spread to other Kashima schools such as Kashima Jikishinkage-ryu and Kashima Shin-ryu.[1][6]

His experiences, which would climax in his duels with the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, led him to create a set of techniques for the jo and establish a new school which he named Shinto Muso-ryu.[1][2] The techniques were intended to be used against an opponent armed with either one or two swords.

Among the advantages of the Jo is its superior length when matched against a sword. The extra length enables the wielder to keep the swordsman at a disadvantage and this is frequently applied in SMR.[1][2]

Muso Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi [10]

The legend states that Muso Gonnosuke fought two duels with Miyamoto Musashi and was defeated in the first, but victorious in the second, using his newly developed jojutsu techniques to either defeat Musashi or force the duel into a draw.

The first duel is described in the annals known as Niten Ki,[1] which is a list of anecdotes told about Musashi and compiled by Musashi’s followers after his death.[7] The Niten Ki describes the first duel to have taken place c.1610.

One of several legends states that after his defeat Gonnosuke withdrew to the Homan-zan mountain in the northern part of Kyushu, spent his days meditating and training, and underwent austere religious rituals.[7] There are several stories about how Gonnosuke received a vision of this new weapon, the Jo.

Miyamoto Musashi [10]

While resting by a fire near Kamado Jinja, Gonnosuke heard a voice say “Be mindful of the strategy ‘the moon reflected in the water’ (suigetsu)”.

In another, after one of his regular (exhausting) training sessions, he collapsed from fatigue and reputedly had a vision of a divine being in the form of a child, saying to Gonnosuke: “丸木を以って水月を知れ” – maruki o motte suigetsu o shire” – “Using a round stick, know the solar plexus”. [9]

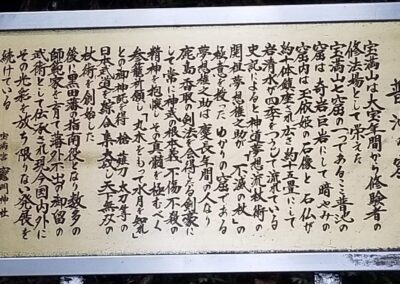

Fuchi no Kutsu 普池の窟 (Fuchi Cave) on Mt. Homan, where Gonnosuke engaged in austere practices.

Permanent sign of historical information outside of Fuchi no Kutsu. Click images to expand.

Gonnosuke took it upon himself to create the jo deliberately longer, at 128 cm, than the average katana of the day (maximum length of a katana set by Tokugawa law – Buke Shohatto, at approximately 100 cm).

Gonnosuke used that Jo length to his advantage in a fight. The tradition states that was his inspiration to develop his new techniques and to fight and defeat Musashi during their second encounter.[1][2] It should be noted that Gonnosuke spared Musashi’s life.

After the creation of his jo techniques and his establishment as a skilled jojutsu practitioner he was invited by the Kuroda clan of northern Kyushu (in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture) to teach his jojutsu to their warriors. Gonnosuke accepted the invitation and settled there.[1]

The Secret Art of the Kuroda Clan (1614 – 1871)

After Gonnosuke’s death, his jojutsu would become a closely guarded secret (oteme-waza) of the Kuroda clan, and forbidden to be taught anywhere but within its domain and only to specially selected people within the warrior-class.[1] This was not an unusual practice in the Edo period.

The main students of Gonnosuke’s art were the men charged with policing the Kuroda clan’s domain (Kuroda-han). During this period other schools (ryu) were created and taught in the Kuroda-han and in the various branches of the Shinto Muso-ryu system.[1]

During this period, two newly created schools which included the art of the police baton (jutte), and the art of restraining a man with rope (hojojutsu), were taught within the branches of the Shinto Muso-ryu as a complement to the arresting arts (tori-te).

Fukuoka Castle [11]

After Gonnosukes death the art was mainly transmitted by the “Dangyo-shiyaku” (men’s arts instructor[1]), though not all branches of the Kuroda staff-traditions used the title of Dangyo-shiyaku.[1] The Dangyo-instructor position was, unlike the swordsmanship instructor (kagyo) a non-hereditary position[1] within the hierarchy of the Samurai.

The Dangyo-instructor in the Kuroda-domain was the charged with teaching the lower ranking warriors (ashigaru) in the arts of the staff (Jo), capturing/seizing/escaping (torite), gunnery (hojutsu) and rope (nawa)[1] among other martial arts. The position of Dangyo-instructor lasted until the abolishment of the Samurai and the feudal system in the 1860s-1870s.

Over time there would arise seven different lineages from the main Shinto Muso-ryu system.[1] These are collectively known as “The Staff of Kuroda” (Kuroda no jo). Of these seven branches of Gonnosuke’s jojutsu, only two would survive the ending of Japan’s feudal system in 1867 and the resulting socio-economic modernization, to be informally merged into a single line that is today the modern “Way of the Gods School of Muso” ( 神道夢想流 Shinto Muso-ryu ).[1]

The first split in the SMR occurred after the death of the fourth headmaster Higuchi Han’emon.[1] The split was the result of one of his licensed (menkyo kaiden) students, Harada Heizo Nobusada, breaking away to establish the “New Just School of Muso” (新とう夢想流 Shinto Muso-ryu) (later informally known as Kansai-ryu), while another licensed student of Higuchi Han’emon continued the original “True Path” line (later known as Moroki-ryu).[1]

For several years Gonnosukes art was passed on by these two lines. The “New Just” line continued until after the death of its headmaster Nagatomi Koshiro Hisatomo in 1772.[1]

Afterwards, the “New Just” line branched off into two separate traditions.[1] The primary reason for this branching, though indirectly, was the result of a restructuring of the living and training quarters of the warriors at the Chikuzen castle. The low-ranking foot soldiers (ashigaru) and the junior officers (kashi) were relocated to two separate areas of Fukuoka, partially due to the difference in the social status of the two groups.[1]

Each group would create new centers of training in their respective areas. This led to the establishment of two new branches from the “New Just”-line of jojutsu, each under their own respective head instructor.

These new lines were named Haruyoshi, led by Ono Kyusaku, and the other Jigyo, led by Komori Seibei, respectively. The two branches were named after the two respective areas of the castle (Maizuru Jo – 舞鶴城 ) in which they trained.[1]

Fukuoka Castle & Haruyoshi Gate/Area [13] – click for larger image

These new branches, Jigyo and Haruyoshi, were a reality by the early 19th century, but even though separate, all three lines appear to have been very similar in terms of techniques.[1] This was demonstrated when the Jigyo Branch was broken with the death of its head instructor Fujimoto Heikichi in 1815.

Because of this, the Jigyo found itself without a fully licensed headmaster, [1] and without a successor from within its own organisation the line would have died out. However, Hatae Kyuhei, who held a full license in the Haruyoshi branch, would eventually revive the Jigyo branch and allow it to continue into the Meiji period (1868–1912).[1]

Meanwhile, the “True Path” had also fallen onto hard times as the tradition was broken with the death of Inoue Ryosuke in 1831. The similarities between the various “Staff of Kuroda”-traditions were again made clear when Hatae Kyuhei (who was an exponent of the Haruyoshi-branch and had also helped revive the Jigyo branch of the “New Just line”) revived the “True Path”.

The “True Path” would, however, become extinct in the Bakumatsu era (1850–1867).[1] It was not until 1871 that the ban on teaching outside the Kuroda clan was lifted.

Fukuoka Castle [13]

Shiraishi Hanjiro and the post-Kuroda period (1871- 1927)

With the abolishment of the shogunate in 1868 and easing of bureaucratic restrictions, Shinto Muso-ryu (and all the other martial arts of the land) was allowed to be taught outside the traditional family lands.

Despite this new-found freedom, however, it meant that the numerous economical benefits and patronage, which was a part of the traditional clan system, were abolished along with it.

Because of this the numerous menkyo holders of SMR who had depended on the old system for financial support had no choice but to adapt themselves to this new Japan. Many of them left the traditional clan holdings, where their ancestors had lived for centuries, and made new lives and livelihoods for themselves.

The final abolishment of the warrior-caste and the feudal-system also led to a rapid modernization of Japan. During this era many of the old bushi (Samurai warriors of all ranks) had no choice but to abandon the old (and considered by most of the Japanese population of the time to be all but obsolete) martial arts altogether.

Throughout Japan most of the surviving traditions were kept alive, if only barely, by the former samurai and other enthusiastic individuals, the former which now had to find a new place (and a new source of income) in the new Japan, which frowned upon the old samurai way.

Some of the old ryu, who were not as dependent on old samurai government sponsorship as others, fared better than others in the transition from samurai to the Western-style government.

During this transition period and beyond, various groups of former Kuroda bushi held sporadic meetings and training sessions in memory of the now bygone era. The old bushi present at these sessions included Uchida Ryogoro, Shiraishi Hanjiro and many of the former Dangyo (instructors) of the Kuroda clan.

Due to newfound cooperation between the surviving SMR-lineages there were several joint-licenses of the Haruyoshi and Jigyo-branches of SMR issued in the late 19th century. Shiraishi Hanjiro was one of those men who received a full Menkyo Kaiden license.

By the end of the Meiji era, (1912), only Shiraishi was still active as a fully qualified exponent and dedicated teacher of the last two remaining Kuroda Jo lineages.[1]

Shiraishi Hanjiro was born in 1842 and was a lower class samurai. As a bushi, (collective name for all samurai warrior of all ranks), he learned jojutsu, kenjutsu and other warrior-arts as was expected of a samurai.[1]

After the fall of the samurai government, Shiraishi did his best to sustain the jojutsu tradition he had learned. He helped organize the post-samurai meetings and training-sessions of old Kuroda-warriors and would receive his full license in SMR-jojutsu during one of these sessions.[1] Shiraishi eventually opened up a dojo in Fukuoka City and taught the art there.

Sometime in the late 19th century, Shiraishi started learning the art of Kusarigama (chain and sickle weapon) as taught by the Isshin-ryu tradition.[1] He would eventually receive a Menkyo Kaiden in this system and started teaching kusarigama-jutsu alongside jojutsu in his Fukuoka dojo.[1] Shiraishi would award Menkyo Kaiden to several of his jojutsu students who carried on the tradition as a side-art (heiden bujutsu) to SMR-jojutsu.

Shiraishi’s dojo was located in then Hakata City. In 1876, Hakata City and nearby Fukuoka city was merged into a new city named Dai-Iti-Dai-ku (第一大区) and in 1878 further renamed as Fukuoka-ku (福岡区) by the Fukuoka Prefectural government.

Shiraishi would teach Shinto Muso-ryu there until his death in 1927.[1] Shiraishi’s senior, Uchida Ryogoro, decided to travel to Tokyo and teach and expand the art there while Shiraishi stayed in the designated Shinto Muso-ryu headquarters in Fukuoka.[1]

In the early 20th century Uchida Ryogoro arrived in Tokyo and set up shop, teaching Jojutsu to high-rankers in the Japanese society at the time. His students included Nakayama Hakudo (1873–1958),[1] founder of Muso Shinden-ryu, and Komita Takayoshi, founder of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (“Great Japan Budo Preservation Society”).[1]

It was during this time that Jigoro Kano was first invited to Fukuoka to observe SMR which would herald the cooperation between the two arts in Tokyo.[1] Uchida Ryogoro also taught at the Naval Officers Club and later at the Shiba Koen park. Ryogoro’s son, Uchida ryuhei, joined him in Tokyo and studied under his father there and was instrumental in developing his father’s TanJo-jutsu art into a working set of techniques.[1]

Uchida Ryogoro died in 1921. Uchidas efforts in Tokyo greatly assisted in establishing a connection with the various martial arts communities already based in Tokyo and would help pave the way to Shimizu Takaji’s own efforts at popularizing SMR and establishing a new SMR presence.

Shiraishi Hanjiro (1821-1927) [10]

Uchida Ryohei, son of Uchida Ryogoro [12]

Shimizu Takaji era (1927-1978)

Shimizu Takaji was born in 1897 and came from humble origins, his family descending from a line of village headmen and minor officials.[1]

In the aftermath of the abolishment of the samurai caste, Shimizu’s father would manage a small general store while Shimizu, after graduating from elementary school, took employment in a small factory at Hakata, where the Shiraishi Dojo operated.[1]

Shimizu started his training at the age of 17 (1914) under Shiraishi himself and quickly rose in the ranks, receiving the Mokuroku scroll in 1918 and the license of full transmission (Menkyo Kaiden) in 1920 at the age of 23.[1] Of the many students of Shiraishi there were three who became prominent in the aftermath of Shiraishi’s death. Shimizu Takaji (1898-1978), Takayama Kiroku (1893–1938) and Otofuji Ichizo (1899–1998).[1]

In the early 1920s Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, witnessed a demonstration of SMR and made an invitation to Shiraishi come to Tokyo and teach SMR there. Due to his advanced age Shiraishi declined to come in person and sent his student Shimizu Takaji instead.

Shimizu arrived in Tokyo in 1927. After a further demonstration of SMR-jo in front of the Tokyo Police Force technical commission, a decision was made to incorporate elements of SMR-jo for police-use.[1] The new system was named keijo-jutsu and intended for use with the special police unit Tokubetsu Keisatsutai.[1]

Shimizu started training the new unit in 1931. Now a permanent Tokyo-resident, Shimizu opened up his own dojo, the Mumon (No Gate) Dojo.

In 1929 Takayama Kiroku, with financial aid from the family of the late Shiraishi Hanjiro, opened a dojo in Fukuoka [1] and was named Shihan with Shimizu named fuku-shihan or “assistant master”. Shimizu by this time, however, was on his way to Tokyo in order to teach jodo.

Takayama died in 1938 and Otofuji Ichizo took over as the new master of the dojo and of the Fukuoka-jo, a responsibility he held until his death in 1998.[1]

During the 1930s in Tokyo, Shimizu felt that the traditional way of teaching Jo was not suited for this new (and more numerous) generation of students. He realized that a better method of teaching Jo was required in order to properly teach ever increasing number of new students who had no previous experience of martial arts.

Shimizu took inspiration from Jigoro Kano’s new Judo organisation and training-methods in order to, among other things, develop the twelve basic techniques kihon which would make SMR more appealing and approachable to the beginner-student.[1][2]

These twelve basic techniques are still taught in most mainstream dojos today. In 1940 Shimizu became the head of the Dai Nihon jodokai (Greater Japan jodo Association)[1] and he decided to rename the art from Jojutsu to Jodo in keeping with the trend of the time.

With the end of World War II in 1945, many martial arts were banned by the new government for fear that they might be used by ultra-nationalistic groups as a way to cause civil unrest.[2]

The police-jo taught by Shimizu to the Tokyo Police force was one of the few exceptions and many other martial arts practitioners from before the war went to Shimizus dojo in Tokyo for training.[2] The police-jo were further developed in the 1960s when it was adapted for use in crowd-control with the Tokyo Riot police.

Shimizu, as had Shiraishi before him, has both been described as an SMR Headmaster due to their initiative and major contributions to SMR though neither Shiraishi or Shimizu received official appointment to such a position.[1]

Shimizu would complete Shinto Muso-ryu’s transition from a localized bugei ryu to a national martial art and become the art’s greatest popularizer through his acceptance of foreign students and the establishment of jodo-organisations.[2]

Shimizu Takaji (1898-1978) [16]

Police at Koban with Keisujo [14]

Post-Shimizu Takaji era – 1978 to present

After the death of Shimizu Takaji in 1978, SMR in Tokyo was left without a clear leader or appointed successor. This led to a splintering of the SMR dojos in Japan, and eventually all over the world. With no single organisation or individual with complete authority over SMR as a whole, several of the various fully licensed (menkyo kaiden) SMR-practitioners established their own organisations both in the West and in Japan.

From the end of the Samurai reign in 1877 to the early 20th century, SMR was still largely confined, (though slowly spreading), to Fukuoka city on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu where the art first was created and thrived.

The main proponent of SMR in Fukuoka during this time was Shiraishi Hanjiro, a former Kuroda-clan warrior (ashigaru), who had trained in and received a joint-license from the two largest surviving jo-branches of SMR.

Among Shiraishis top students were Shimizu Takaji, Otofuji Ichizô and Takayama Kiroku, Takayama being the senior. After receiving an invitation from the Tokyo martial arts scene to perform a demonstration of SMR, Shimizu and Takayama established a Tokyo SMR-group which held a close working relationship with martial arts supporters such as Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo.

Shiraishi died in 1927 and there now existed two main lines (or branches) of SMR. The oldest of the two was found in Fukuoka, now under the leadership of Otofuji with the one in Tokyo under Shimizu.

Takayama, the senior of the three students of Shiraishi, died in the 1930s leaving Shimizu with a position of great influence in the SMR-scene as the senior-most student of Shiriashi, (Otofuji being his junior), that would last up to his death in 1978.

By the 1970s the Tokyo and Fukuoka SMR-communities had fully developed into separate branches with their own leaders. Shimizu was a senior of both the Fukuoka and Tokyo SMR, with great knowledge and influence over both.

Otofuji would remain the leader of Kyushu SMR until his death in 1998.

Otofuji Ichizo (1899–1998) [16]

From these two lineages, the Fukuoka and the Tokyo, there stems today several SMR-based organizations all over the world. One of the largest is the All-Japan Jodo Federation (ZNJR), established in the 1960s as a branch of the All-Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR – Zen Nihon Kendo Renmei).

The ZNJR was established to further promote Jo through the teaching of ZNKR Jodo, also called Seitei Jodo. Seitei Jodo remains the most widespread form of Jo in the world today.

All Japan Kendo Federation – Seitei Jodo [15]

References

1. Matsui, Kenji. 1993. The History of Shindo Muso Ryu Jojutsu, translated by Hunter Armstrong (Kamuela, HI: International Hoplological Society)

2. Krieger, Pascal – Jodô – la voie du bâton / The way of the stick (bilingual French/English), Geneva (CH) 1989, ISBN 2-9503214-0-2

3. Muramoto, Wayne: Nishioka Tsuneo and the Pure Flow of the Jo

4. Risuke, Otake (2002). Le sabre et le Divin. Koryu Books. p. 31. ISBN 1-890536-06-7.

5. Watatani, Kiyoshi. Bugei Ryuha Daijiten. Tokyo Koppi Shuppanbu, Tokyo, Japan, 1979 edition. p. 426.

6. Muromoto, Wayne. Muso Gonnosuke and the Shinto Muso-ryu Jo

7. Lowry, Dave The evolution of classical jojutsu, 1987

8. Taylor, Kim. A Brief History of ZNKR Jodo, Journal of Non-lethal Combatives, Sept 2000

9. Muso Gonnosuke

10. History of Shinto Muso Ryu

11. Fukuoka Castle

12. Uchida Ryogoro

13. Fukuoka Castle – Maizuru Jo 舞鶴城

14. Police at Koban with Jo

15. AJKF Jodo Contest

16. Asakichi Nakajima & Tsunemori Kaminoda. Jodo Kyohan. Japan Publications Inc. 1976, ISBN4-8170-6415-3 C0075